Building Better Connections: Part 2

2019-09-03 · Posted by: Justin Cappos · Categories: Informational · CommentsIn my previous post, I described how industry participants and academics within the computer systems field have very different understandings of the world today, and rarely interact at common venues. This post takes a look at one potential reason for such a gap:the differences in how academics and industry value a project. I also offer some suggestions for finding common ground for sharing expertise and ideas.

Why do academic and industry conferences value different types of work?

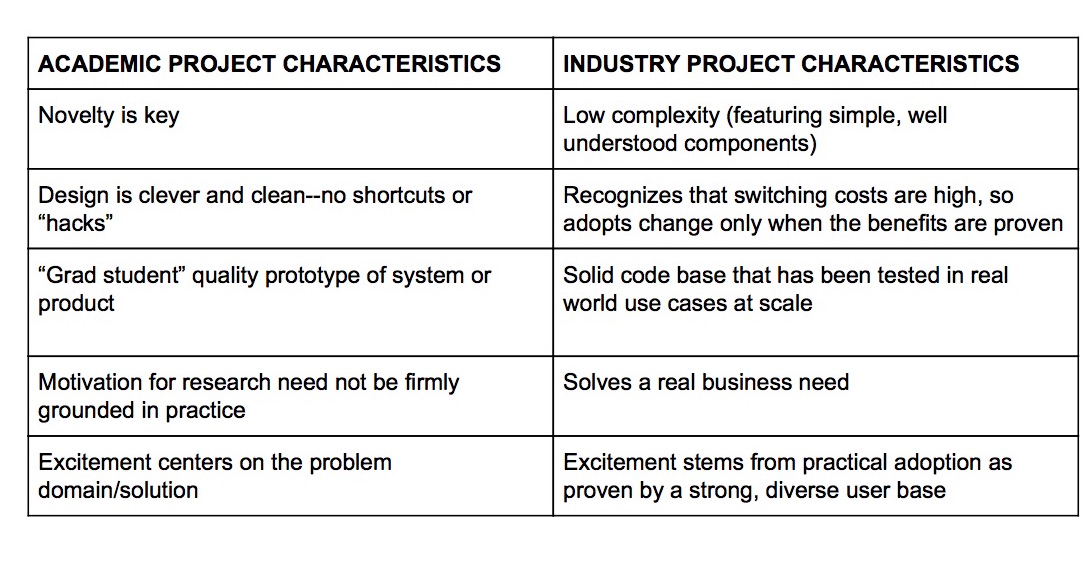

Put succinctly, academia and industry professionals value different types of research, and this creates very different criteria for selection of presentations for conferences and journals. (This remains true despite the fact that both types of conferences are often equally rigorous, with an acceptance rate of ~20% at top venues for both.) To address the gap between these two worlds, it is important to be aware of what excites researchers in each arena. The table below summarizes the characteristics of papers presented to academic vs. industry audiences. These points are discussed further in the next two subsections.

What Academia Values in Research Papers

So, what do academics value in a research project? A near universal reviewing category for computer science conferences is the novelty of the work. In my experience, the novelty score has a high degree of correlation with whether or not a paper is accepted. “Novelty” here means the paper is defined as sufficiently “different” and “unique” in comparison to prior work that other academics have done on the topic. Work that builds on existing products or technologies is likely to be described as “incremental,” which is a dirty word in academia and, for many reviewers, a strong basis for rejection. Hence my group typically rebrands systems with a new name for each publication to make them seem newer to the academic community (of course while still clearly describing the differences between this and our prior work).

This relentless drive to produce something “new” can, unfortunately, detach the research initiative from any type of practical application. The academic stereotype of having “a solution looking for a problem” does sometimes apply in practice (including in some of my early work). Many academics specialize in techniques (i.e., machine learning, cryptography, blockchain, etc.) instead of problem domains (i.e., securing healthcare, improving cloud native services, etc.). This could lead an academic to apply their technique to a domain in which they are not experts. The lack of expertise leads to misunderstandings about a problem domain. Solutions forged out of confusion can never be applied in practice, since real world constraints have not been considered. It is quite rare to have academic code actually used in production before publication, except perhaps in the form of a very early stage “prototype,” and an actual deployment in a real environment is even rarer still. For example, of the 45 papers presented at NSDI 2016, the only major systems conference with a track soliciting operational experience, only 7 described a production deployment. Five of those with deployments were from technology companies, Microsoft, Conviva, Facebook, Baidu, and Google, and so did not release source code. (The lack of source code is a noted problem in our field since it may make it more difficult for other researchers to replicate the results.) Our paper in that conference was one of only two that described a system used in production, and that released its source code.

Further compounding this disconnect from practical problem solving is that the motivation for most academic work, and/or the problem to which it is matched, usually comes from prior academic papers. Without validation through a real world deployment, the assumptions behind earlier work is rarely challenged. After all, the academic researchers who wrote the cited paper obviously thought the motivation and problem constraints were real enough for them, and they are likely to be among the reviewers for the new paper. This runs the risk of compounding and propagating errors made by other academics.

Another characteristic of conference papers based on academic research projects is a certain amount of unwarranted exuberance about the potential impact of the work in order to increase the “buzz” surrounding it. Academic research projects often tend to hype the potential impact of the work by using jargon that adds little to any meaningful discussion of what the process or product actually does. My experience has been that few academics want to read a paper about “improving the security of the software update process.” It is much more appealing to read a paper about a “compromise-resilient, community-repository aware, cloud native software update framework,” even though these two papers describe exactly the same system.

Buzz is likely to grow louder if the solution involved is deemed “elegant.” Clever design ideas also tend to be a major factor in paper acceptance. If a “hack” is needed to make something work, this is often viewed as a blemish, and so will likely be glossed over or excised from a paper. Unfortunately, making software work often necessitates such tweaks, hacks, and changes. And, making software work in a real world environment will likely require more “hacks” From a purely academic standpoint, this effort is not at all worth the additional likelihood of paper acceptance.

Lastly, in academic papers, the code behind the product or technology presented is generally treated as less important than the idea it supports. The term “grad student code” is effectively a shorthand for undocumented, buggy, partially-implemented software. Recent efforts to reproduce academic results using the software provided by researchers confirms how rudimentary such code tends to be. For example, in 2011 FSE, a top software engineering conference, had a 50% replication ratefor academic papers amongst those paper authors who chose to have their results replicated.

Of course, the lack of reproducibility has not gone unnoticed. There are some excellent efforts ongoing to combat this issue. The ACM launched an initiative to attempt at least “weak repeatability” of the results of 601 papers published in the association’s conferences or in their journals. “Weak repeatability” was defined simply as “do the authors make their source code available, and will it build?” The study’s overall conclusion was that only 32 to 54% of the research presented in the paper could be reproduced, depending on what classification of “reproducible” was applied. When speculating on why this was the case, the article cites an earlier paper whose author summarized the profession’s attitude as follows: “Innovative findings produce rewards of publication, employment, and tenure; replicated findings produce a shrug.”

While achieving reproducibility and the transparency needed to address the problem is a very complex issue, and any potential solution is beyond the scope of this document, one could argue that strong ties with industry might be a good first step. When working alongside individuals for which the ultimate criteria for any proposed solution is “does it work?,” reproducibility is likely to place somewhat higher in a researcher’s priorities.

What Industry Professionals Value in Research Papers

The best industry research papers largely mirror what practitioners value in a piece of software. This means industry-based conferences seek presentations that have, at their core, a stable, working product that solves a real problem.

The quality of the code base and community of the system described in a presentation is paramount. Software must be engineered in a way that is maintainable. The developer should follow reasonable code style guidelines, reviews must be performed, and all work on the code, including patches or updates, must be well-documented. This attention to code quality is particularly crucial for open source software because a company that deploys a product is committing to fix whatever issues arise in their deployment.

Another hallmark of industry papers is that the technology used as components of a system should be proven, simple, and well understood. ;login: Spring 2019 had an article titled “Achieving Reliability with Boring Technology,” that described the desire of most developers for a solution proven to work. Risking your company’s fortune or your job on experimental technology is a good way to end up unemployed. What all of the above suggests is that industry has much less tolerance for novelty. For industry, version 2.0 of a popular, useful piece of software is much, much more attractive than any new piece of software.

Related to its preference for proven technologies, industry research initiatives embrace an attention to a piece of software that carries through to the maintenance stage of its lifecycle. How actively a piece of software is maintained is a key to its value. This is often evaluated by looking at the userbase of a product. If it is being used in production by a substantial number of invested participants, then it is likely that bugs will be fixed and features will be regularly added without the company’s direct involvement. All companies that use the software will improve it, and all will collectively benefit. So a large, invested userbase is a telling indicator of what industry values. Many companies will not use code that does not have one. This is a clear indicator that industry values proven reliability over novelty or elegance.

Another hallmark of industry research is that its criteria for adoption is the ability to solve a real world problem substantially better than the existing state-of-the-art solution. There are often multiple ways to solve a problem, including non-technical procedures. Industry concerns will compare costs and risks to their current practices before considering adoption of something new, but it is rare to see an academic paper that quantitatively examines the legal, business, insurance, certification, etc. differences involved in adopting a new technology.

The factors mentioned above acknowledge that switching technologies always has costs and poses risk. Even if you give a tool away for free, getting people to understand how it works, how to set it up in their environment, etc. is a non-trivial undertaking. It can be extremely time consuming, costly, and challenging to get parties to adopt even widely used, secure, professionally engineered software. Having legacy code makes it very hard to move adopters to a new technology, especially when their existing system “just works.”

It should be obvious from the differences in priorities between industry and academic practitioners that connecting researchers on both sides of the divide will not be simple. In the next section, I present some don’ts and do’s for building bridges and encouraging effective technology transfer programs.

How not to support technology transfer

I have seen a few patterns that do not work well for technology transfer:

-

“Open sourcing it” by placing graduate student code on a website. What company will spend engineering time going through academic websites and code to try to see if there is a useful prototype? Even if the code is cleaned up, without a meaningful user base or solidly engineered codebase, there is little chance of transfer.

-

Expecting industry to communicate their problems to academics. From what I have seen, industry’s goals when working with academia are first and foremost to get high quality interns they can hire to help address the talent shortage. The second goal is to explore “far out” areas and concepts to mitigate and understand long term risk. In other words, should Company X examine using an IoT-hosted quantum homomorphic blockchain? Nevermind that Company X’s business involves making shoes. If a manager there read an article about how technology is changing, they don’t want to have a startup come out of nowhere to take their business (such as when streaming services eliminated the need for video stores like Blockbuster).

-

Taking existing academic work and transferring it. For the reasons discussed above, a substantial part of the academic literature does not connect well with existing problems and scenarios in industry. No matter how well engineered the software is, if it does not solve a real world problem in a meaningful way, it will not get traction. It is uncommon for an academic team to go through the exercise to find “product market fit.” Even if academics want to give away the technology for free, if it doesn’t solve a real world problem much better than existing technologies, the switching cost will outweigh the benefit.

How can we work toward practical impact / technology transfer

-

First and foremost, we begin by working in practice with industry. This means actually using industry tools and techniques in a real world context. The goal here is to really understand the technical problems inherent in the industrial space in which we are working. We need to see the total landscape of stumbling blocks and workarounds that practitioners must navigate to understand the actual goals and constraints in the environment. Often it is possible to get this experience by collaborating closely with practitioners, such as by working together on aspects of a widely-used open source project. However, the goal of such a collaboration should be to better understand the space, not to transition a specific technology or project into use. Contributing in an altruistic way is also an important way to build credibility within the broader community.

-

After you really understand a problem domain, look for opportunities to improve the system in a substantial way. In my experience, dealing with issues that are minor pain points for a lot of adopters is perhaps the easiest way to go. (For example, I’ve worked a lot on the security of software update systems, which isn’t something any company competes on, but everyone desires to some degree.) These sorts of pain points are often invisible to individual users because they are such a small part of every effort. Yet, building an effective solution to such problems gives one a broad potential userbase.

-

Work altruistically with many potential adopters. Individual companies and organizations have their own priorities, and those priorities have a way of shifting. One of the first major groups to recognize the value of TUF was the Python community. In 2013 and 2014, we worked with the Python packaging community to create PEPs (Python Enhancement Proposals) for two different deployments of TUF. This work generated quite a lot of positive discussion in the Python community that spread to the broader tech community. In that timeframe, however, Python was in the process of moving to a new version of their repository software and so wanted to complete this process before integrating TUF. As a result, as of August 2019, the Python community still has not integrated TUF into production use, although it appears that work may be starting now. Yet, the discussions and awareness generated by our work with Python led to several other communities integrating TUF, like Docker. After Docker’s integration, many other adoptions followed in the cloud space, including Microsoft Azure, Oracle, Cloudflare, Digital Ocean, RedHat, IBM, Datadog, and others. I believe it is much less likely this would have happened without the discussions in the broader community, which were followed by Docker’s security team. We worked with many different adopters and listened to their problems and concerns to help speed this transition along.

-

Expect the process to take awhile. Unfortunately, transitions into an existing code base often take many iterations with potential adopters before they are used. It took nine attempts before our patches, which produced a new signing model for git and fixed serious flaws, were adopted. This is surprising, given that they were done by a member of Arch Linux’s security team who has fixed serious flaws in many other pieces of software! In another example, a bug in the networking library for Python took several years to fix, despite the fact that a detailed description and a patch for the bug were provided. Software projects have their own timelines and goals, so you need to be engaged over a period of time. You are effectively asking them to understand, approve, and then agree to maintain the piece of code you provide them. So, be understanding when an overwhelmed maintainer isn’t jumping to add your code (and everyone else’s) into their codebase.

-

Engineer software right from the beginning. We have used professional software engineers, followed code style guidelines, employed code reviews, and just had an overall focus on code quality and testing from our early days. This has led to multiple software projects that have been used for up to 10 years, as well as codebases that are reused in production in many domains. If you do not create software that is ready for production use, who will ever use it? Also, it has been my experience that clean up is often more work than redoing the effort. Be wary of “I’ll test it later” or the even more worrying cry of “I’ll comment it later.” This is a recipe for buggy software that can impact the performance or security of a product, or just produce false results overall. We worked on several pieces of research code with bugs that would have substantially changed our results had we not caught errors when with testing. Of the five papers by other authors I have replicated, I found errors in four of them. Correct software engineering is paramount for the accuracy, reproducibility, and production use of software.

Conclusion

If you would like to add your insights to this discussion, we encourage you to join our Google group. Conversations in this group could suggest tangible actions to move industry/academia interaction forward.