Building Better Connections Between Systems Researchers and Practitioners

2019-08-12 · Posted by: Justin Cappos · Categories: Informational · CommentsAcademia and industry traditionally play complementary roles in the advancement of scientific and engineering knowledge and in the development of useful products to benefit society as a whole. While industry, tied as it is to a bottom line, typically focuses on the problems of today, including how to bring products to market, academia has the freedom to work on risky ideas that may require years of effort but have a high payout if successful. With funding from government agencies to fuel academic efforts, innovation can proceed at a faster, more advanced pace. Industry can then take the ideas from academia and expand the reach of the technology even further by using it as the basis for practical applications. In turn, this leads to more progress which raises more tax revenue than the government invested — or at least this is the dream.

It’s a dream that has worked very well in some scientific disciplines for many years. Unfortunately, there is a bit of disconnect between academic and industrial practitioners in some fields, including the field of computer systems, that makes such reciprocal relationships harder to achieve. This disconnect is caused, in part by a lack of “common grounds” for sharing ideas and developing potential collaborations. Industry participants comprise only a small percentage of attendees at academic conferences, even if one counts attendees from research labs. This impression is bolstered not only by a short survey we recently conducted (discussed in greater detail below) in which roughly half the respondents from industry did not know what OSDI was, but also in a presentation by noted software engineer Bryan Cantrill who, in 2004, found himself the only industry-based presenter at USENIX ATC.

Conversely, academics also make up only a small percentage of industry conference attendees. In our study, only 8% of the academics participating in our study knew that Kubecon was the largest open source software conference. Perhaps unsurprisingly, despite substantial effort (including over $82.5 billion of government funding in calendar year 2015 alone) for technology transfer, academic based initiatives are facing some challenges in making the “dream crossover” outlined above.

This perceived disconnect is one that must be resolved if the computer systems field is to create the symbiotic relationships that have benefited scientific disciplines in the past. This article explores some potential causes for this disconnect. Given that a recent study of economic benefits derived directly from academic-industry patent licensing reported that between 1996 and 2013 such efforts, “grew US gross industry output by up to $1.18 trillion and US gross domestic product by up to $518 billion, and supported more than 3.8 million US jobs,” resolving the disconnect should be a priority for professionals on both sides of the divide.

Note that this blog post focuses specifically on the systems and systems security communities,where researchers build software that they hope industry will utilize. This is notably different from fields where the data is the interesting part of what is being studied (such as privacy research) or where the mathematical properties of the research are the primary outcome (such as theoretical computer science). Hence, the observations made here may not apply to other fields.

Do academic and industry researchers in computer science see the world the same way?

To confirm what was initially just an observation, about the differing perspectives of academia and industry, I created a survey that asks some basic questions about a few different systems technologies and conferences. The survey has 3 questions about conferences, 3 about technologies, and 4 questions about the importance of certain technologies in practice, along with 3 demographic questions to determine if the participant was a developer, graduate student, professor, etc. This survey was sent out to systems researchers who publish in the systems security space, and to industry personnel in the cloud-native community. Participants were asked to share the study with others who work in a similar role.

After sending out the survey, we received 80 responses, 48 of which were from participants who said their primary field of work could be described as industry, 26 participants who described their primary work field as academia, and 8 who said their work was an equal mix of both. The findings below focus on the industry and academic participants and ignores the participants who indicated their work was a mix, as this group is much smaller.

Participants were asked not to look up answers or guess randomly, but these properties were not enforced or verified.

As several aspects of the study, such as the participant selection, ability to look up answers, etc. can bias the results, I caution against reading too much into the exact numeric findings. However, the data (raw data is provided here) does suggest some obvious trends.

First, we found some similarities between the groups. The vast majority of academics (96%) and industry participants (83%) were aware that USENIX runs conferences. There was also rough agreement that containerd, the technology that underlies the fundamental cloud technology of containerization, is an important technology, with similar numbers from each group.

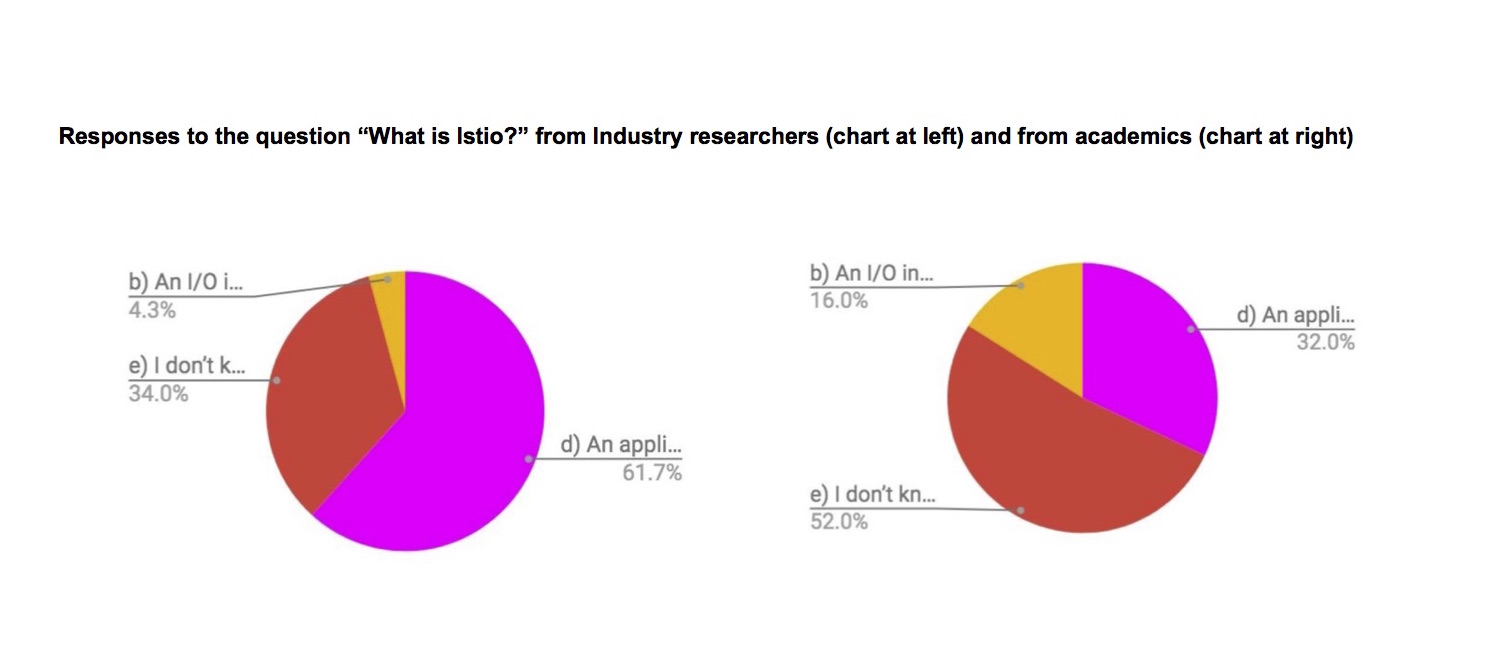

However, there were some major differences revolving around understanding of key technologies. About a third of academics knew that etcd and Istio are two widely used cloud technologies, while about 60% of industry participants knew these technologies. Conversely, 60% of academics knew about MULTICS, as compared to only 38% of industry participants. When asked if a technology was very relevant in practice to many companies, academics thought both Homomorphic Encryption (20%) and OpenFlow (28%) were much more important technologies than their industry counterparts (where both scored only 2.1%). Industry was more aware of rkt (a recently archived CNCF project) and found it more relevant, whereas most academics (72%) were not aware of the technology.

Even more concerning, the numbers for professors were more pronounced than for graduate students. This means professors (who had an average of over 17 years or experience) had a much bigger divergence from industry than students (who averaged about 4.5 years). While a follow up study would be needed to test this, one possible reason for this disparity is that the longer professors are in academia, the more out of touch with industry practices they become.

There were also differences in awareness about conferences. Only 24% of industry participants knew OSDI, one of the most prominent gatherings for systems researchers, was a conference, while 72% of academics polled stated this correctly. While both academia and industry were not overly aware that Kubecon was the largest conference (at least by some metrics), only 8% of academics knew this, while about 30% of industry participants were aware. Participants were asked to list a conference that academics would attend and to list a conference that industry developers would attend. Strikingly, the only conference that appeared on both lists was USENIX, where one of the 80 respondents (a professor) listed it as a place that industry personnel would attend.

One industry participant summed up the lack of interaction between academia and industry as follows: “I just didn’t have the slightest idea of a conference academics would visit. Considering I’m a wannabe-academic, that’s not good.” So despite awareness and a desire to work together, there is still a substantial gap between academia and industry.

Is deep interaction between industry and academia possible in the field of computer science?

There are some fields in computing that have healthy industry-academia interactions, for example the wireless measurement community. Academia was willing to take a chance on the millimeter wave wireless band and it paid major dividends, with the new 5G standards supporting about 1000x better bandwidth than 4G. In addition, many academic researchers and testbeds were heavily involved in helping to form the new 5G specification. Just as in the ideal model framed in the introduction, academia explored a relevant area, with industry heavily engaged from the earliest days to help shape the problem domain. Then, industry commercialized the findings, which led to a major benefit to all smartphone users, more sales of smartphones and equipment, and finally more government revenue from taxes to reimburse initial efforts. Clearly, when the model works, everyone wins!

Why aren’t computer systems professionals in academia and industry talking to each other?

It’s hard for two groups to talk if they don’t occupy the same space. As started earlier, academic researchers are essentially nonexistent at major industry conferences focused on building distributed systems, like KubeCon and DockerCon. Similarly, very few industry personnel show up at academic venues. Without speaking, it is no wonder that there isn’t the degree of interaction between academia and industry that would be desirable.

But, the gap can be bridged with a better understanding of exactly what type of work is exciting and relevant to each of these sides. In Part II of this exploration, I will posit a few reasons why academia and industry may value work differently, and thus may not be attending the same conferences.

Conclusion

This writeup was created to start a discussion about how academics might better collaborate with industry. I’ve created a Google group to further this discussion, where we can discuss experiences, strategies, successes, and failures. I will also be at USENIX Security 2019 in Santa Clara this week and would love to chat with people there in person. I’m curious to hear from others about the extent to which they see the same problem and their attempts (both successful and unsuccessful) to bridge the gap. Most importantly, this forum can provide a place to toss around ideas about how to move forward. Working together on the problem, I’m sure we can greatly improve the state-of-the-art!

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank Lois Anne Delong who helped with the survey and also edited this piece as well as Santiago Torres-Arias, Damon McCoy, and Rachel Greenstadt for their insightful feedback.